The Most Pressing Authentication Processing Pain Points In 2020

Authentication online has become amazingly complex in the last 20 years. What began as a simple password problem in the seventies, is now an opulent buffet of different authentication options together with very real regulatory and security considerations. There is certainly no shortage of ways to sign up or sign in to something!

But what are the most pressing pain points for developers and end-users? What does great authentication look like? What does terrible authentication look like?

To answer these questions, I interviewed ten active members of our development community asking what they think 2020’s most pressing authentication pain points are. Each person I spoke to has a different background in the web industry but each has an active interest in authentication. The result is a collection of opinions and authentication pain points seen from different perspectives. So, let’s dive in.

First of all, the strength of feeling surprised me. I know my question asks you to consider what the pain points are so obviously you’re looking for them but what I hadn’t expected was the amount of pain being felt out there. I expected answers such as: “Well, you know, OAuth is a bit tricky’ but what I actually got was multiple pain points from each developer covering a wide variety of concepts. It strikes me that there may be more broken with authentication than I first anticipated:

“It's expensive and dangerous for me to build my own authentication.” Martin Omander, Developer Advocate at Google.

It’s really difficult for me to be totally sure that my authentication is secure without any vulnerabilities. I always try to follow best practices to be sure that everything is secure but I can’t avoid that little voice in my head saying “you made a mistake”, “your authentication is not fully secure”. Ale Sánchez, Software Engineer at Rebellion Pay.

The problem I see most often is that software developers don’t put authentication in every single place it needs to be. For instance, you have an application that calls an API and there’s no auth (this happens sometimes). Now imagine that API calls another API and there’s no auth there, this happens A LOT. We assume trust between APIs, containers and other services that don’t reach outside our network, which is a big mistake. Every service and application must be its own island, and implement zero trust, by ensuring there is authentication, then authorization, before granting access to anything. Tanya ‘SheHacksPurple’ Janca, Security professional and blogger at SheHacksPurple.dev

This is deeper than I thought we’d go on day one and are just three quotes from my research. Developers go to work to solve problems but we don’t get danger money nor do we get access to counselling if we spend a year worried sick about hackers.

So with that, we arrive at pain point one: Security is an ever-evolving challenge, it’s hard to make authentication secure and to foresee all the ways it might be vulnerable. This makes it expensive to develop, expensive to maintain and high risk for someone to take responsibility when the impact of a bug can be so large.

Using someone else’s authentication instead

Of course, you can avoid rolling your own authentication by using a service.

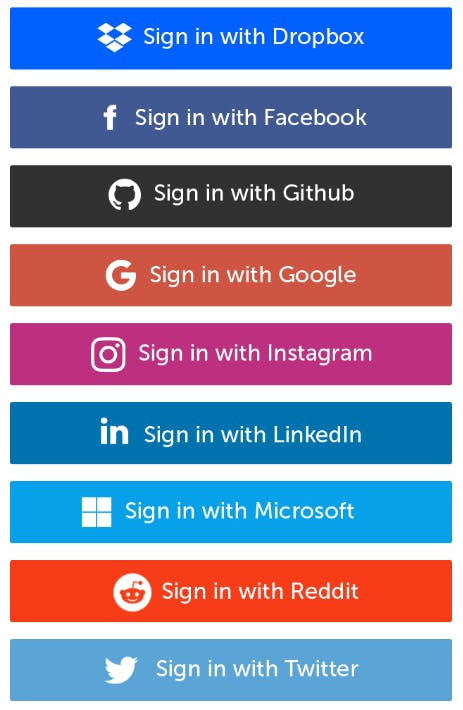

OAuth 2.0 is the open authorization standard used for this. Although OAuth is actually a framework for authorization, it is synonymous with authentication. This is largely because social logins used on websites are implemented using OAuth (and usually OpenID Connect too). ‘Signing in with Facebook / Google / Twitter / Github’ is the norm for millions of users. Some sites, for example dev.to, don’t offer anything else except sign in with Twitter or Github. We have become reliant on these social networks managing our identity for us and while this is a big win (let someone else figure out the hard stuff!), there are downsides too:

Being able to use an OAuth provider, along with the proliferation of good password management software, is a huge win for developers and users alike. I believe that authentication will become exponentially easier as services that simplify the authentication process become available. One downside of OAuth is that we spend less time developing our own authentication, but spend more time understanding and implementing third party solutions. The biggest pain point of authentication in 2020 is that last piece: OAuth. While extremely convenient, it is a process that could be improved. Aimeri - Full Stack Developer, NC USA.

So in effect, have we swapped one problem with another? Are we really any further forward? OAuth documentation isn’t for the faint hearted. In addition, to offer multiple sign in solutions we need to consult the documentation for each provider. For example, here are all 1830 words of Github’s ‘Basics of Authentication’ guide.

In some cases you’re caught between a rock and a hard place as Yubraj, a FullStack Developer at Etribes describes, when the client demands SSO but without using a third party:

It is difficult to implement one-time login if you don't use thirty party authentication service, I had to go through maze documentation of one of my client's authentication service, it was horrible to test. I had lots of confusion initially understanding OpenId vs OAuth.

Authentication pain point number 2: Third parties carrying out authentication for us are convoluted to integrate with since each one does things slightly differently within the OAuth 2.0 framework. Time is spent working out how to integrate with Facebook, Twitter, Github etc while the need to provide non-branded sign in for users that don’t have accounts with the third parties still exists otherwise you force users to create Github accounts (for example) before they can create an account on your website.

A surfeit of choice

There are some well-known providers that offer to handle identity provider integrations for you. I spoke to Yann in Montreal, a software engineer at PivoHub. He describes a specific issue with Auth0 where users arriving at your website sign in once with Facebook but later return and sign in with Twitter (or another) and the result is two different accounts even if the user’s email address remains constant:

If you use multiple identity providers and the user uses two different providers with the same email, it will create 2 accounts which is a problem. In order to solve this, you must write some custom code which is pretty annoying. They should have a setting for this.

This led me to think, hang on, is choice a good thing? For end-users, are multiple ways to sign up to or into a website actually good user experience?

Okta proudly display a long list of identity providers that come pre-integrated:

Does this look like good UX to you? I suppose it’s unrealistic to expect a website to want to use all of these at once but even three choices could be problematic. Yann’s anecdote shows users forget which social account they used to sign up and end up signing up twice. This is a pain for the developer and a pain for the user.

Circling back round to the developer’s perspective, Martin (developer advocate at Google) says it’s hard to cater for all the ways a user might want to sign in:

It's hard to provide authentication that all your users will like because they have very different preferences. Some prefer to use their Google or Facebook account across all websites. Others prefer creating a new username+password account for each website they visit, for added security. Many users on phones prefer something that requires less typing, perhaps based on their phone number.

And that brings us to the third authentication pain point: there is too much choice.

Try to cater to all users’ needs and you end up with a list of authentication options as long as your arm. This, in turn, causes choice paralysis and problems in the backend when a user tries to sign in or up multiple times using different identity providers.

Provide too few options and not all users can access your website. We see this in the case of sites that exclusively offer social login and no email based alternatives.

In addition, too many authentication options cause choice paralysis for the user and later, if after a long session, they re-authenticate using a different social network they run into problems.

I got chatting to Diego, a Facebook employee. His views are his own and not those of Facebook. I asked the question: Are social logins a developer's friend? Do they make life simpler? Do they do the opposite? Diego answered:

It depends. Are they making it harder to reason around accounts? Yes. Are they making it harder to store an unencrypted password that will be credential-stuffed into a fake leak that causes mass hysteria? Yes.

Diego’s beef is with the alternative to social login, i.e. username and password setups on every site. So yes, social login is tricky to implement but at least it means you don’t have to store hashed passwords in your database which is a definite plus.

If you do decide to start storing passwords, regulations make storing Personally Identifiable Data risky as explained by Martin Omander, of Google:

Storing PII (Personally Identifiable Data, like name or email address) is risky and increasingly regulated. PII in your database is basically a liability. The easiest way to comply with privacy regulations is not to store any PII at all. How can I do that, but still provide secure authentication?

Martin and Diego’s points go hand in hand. How do we reconcile the gap between these two pillars of authentication, neither of which are ‘perfect’?

Martin again:

I do hear from users every now and then about log-in methods. They say one of two things: 1. I don't want to have to come up with yet another username/password combination. 2. I don't want federated sign-in because I don't want anyone to see which sites I visit. I prefer good old username/password.

These conversations lead me to think that pain point four, is that there is no obvious answer to which authentication method is best. There is always some level of debate required. There is no ‘de-facto’ authentication method that reconciles these problems.

The requirements for authentication seem rather simple in essence:

- Authentication should be secure.

- It should be very easy for a developer to implement secure authentication.

- Authentication should be convenient for the end-user.

Nikola, Director of Engineering at Teltech, summarises it perfectly:

Imho, it still seems that, even though we're in 2020, there's just too much fuss with getting authentication to work. It would be great if you could just call one function and woila 🤗.